Did you know there was a time before government welfare programs? It’s true. People used to take care of themselves, and when they fell on hard times, their families or communities usually stepped in to help.

Of course, some people fell through the cracks. But what if there were a way to use the vast power and resources of the government to save them?

I would like to believe that the welfare state was created with the best intentions, but you know what they say about those. In the more than half a century since the Great Society, we’ve seen clearly that government welfare is not only inefficient but also creates perverse incentives for those who rely on it. We’ve become trapped in a downward spiral where every failure of the welfare state is taken as proof that it’s not big enough or expansive enough, so we need to spend more money and open it up to more people.

In the early postwar period, the typical American household had a father working outside the home and a mother caring for the children. This wasn’t universal, but it was the norm. By the 1970s, the idea of women staying home to raise their children was increasingly seen as old-fashioned and sexist. As more women entered the workforce, the demand for childcare grew, driving up demand for government welfare and subsidies. The rise of single-parent households also increased demand for childcare subsidies.

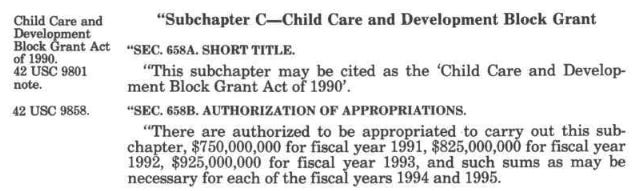

In 1990, Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, which included sweeping changes to the tax code and other regulations. It is most remembered for breaking President George H.W. Bush’s promise not to raise taxes. However, tucked into this omnibus bill was the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), a federal program to subsidize childcare costs for low-income families.

The CCDBG initially appropriated $750 million in grants to be distributed through the states, and that amount has steadily increased since. In 2018, President Donald Trump signed a bill increasing those grants to $2.37 billion, and in 2021, President Joe Biden signed the American Rescue Plan, which included $15 billion for the CCDBG.

Money grows on trees, right?

It’s up to the states to distribute the grants. According to federal guidelines, recipients must have children under 13, be working or in a job training or education program, have a family income at or below 85% of each state’s median income, and have less than $1 million in assets. Additionally, the guidelines recommend that states set payment rates equal to the 75th percentile of childcare providers and require these rates to be updated every three years.

The Idaho Legislature retains the authority to appropriate federal funds for the CCDBG program, but it is administered by the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare (IDHW) under the Idaho Child Care Program (ICCP). For fiscal year 2024, the Legislature appropriated just over $52 million for ICCP, which currently serves 7,800 children in Idaho.

ICCP is just one childcare subsidy available to Idaho families. The Workforce Development Council has limited grants for childcare and there is a state tax credit that can defray costs of up to $12,000 per eligible child.

Last week, IDHW Director Alex Adams informed the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee that ICCP is $15 million over budget this year and is expected to go $22 million over budget next year. Rather than asking for a supplemental budget, Adams said he would work with the department to correct the causes of overspending.

What are those reasons?

Before 2021, Idaho was paying at a level equal to the 65th percentile of childcare facilities in the state. The federal government recommended setting the level at the 75th percentile, so IDHW submitted a program change to set our level between the 85th and 75th percentiles, depending on certain circumstances. This allowed eligible families to receive more money to use at more expensive facilities.

The CCDBG program allows states to set copays for participating families; consequently ICCP uses a sliding scale for copays based on family income. In November 2020, ICCP significantly reduced these copays, in some cases by half, which led to increased expenditures.

Before 2021, the CCDBG program was available to Idaho families living at or below 130% of the federal poverty level. In 2023, IDHW submitted a rule change, approved by the Senate, that raised eligibility to 175%. (It was rejected by the House, but prior to 2024 only one chamber was required to approve administrative rule changes.) This greatly increased the number of families that were eligible for the grant.

Finally, the department updated childcare rates this year, which have unsurprisingly increased by 25% since the last update. This was the only factor outside the department’s control.

In Adams’ letter to JFAC, the director laid out plans to rein in ICCP expenditures by delaying updated reimbursement rates until next year, restoring the pre-2021 reimbursement rates to the 65th percentile of childcare facilities in Idaho, temporarily pausing new enrollments, and restoring the eligibility threshold to 130% of the federal poverty level.

Adams added that ICCP has a rainy day fund of $50 million leftover from previous years which the Legislature could authorize them to spend. He cautioned against simply using this money to supplement the existing budget, saying this would continue an unsustainable path. He instead urged the Legislature to consider ways to use it to expand access while keeping ICCP living within its means.

Over the next few weeks, you will likely hear emotional appeals from activists and news media to simply give this program more money. After all, it’s free, right? The federal government has a giant valve of cash it can open at will, no matter the current $35 trillion national debt. The last time there were questions about the childcare subsidy, protesters crowded the Capitol steps, demanding the cash continue to flow. Our society has long passed the tipping point where everyone believes they have an inalienable right to taxpayer dollars.

Rather than alleviating social problems, government welfare programs enable them. If we allow IDHW to continue expanding eligibility for government grants and continue spending tax dollars subsidizing childcare, then where does it end? Government subsidies create a culture of dependence and distort the market. What kind of perverse incentives are created when a business depends on tax dollars to survive?

Government welfare programs always begin with good intentions, as safety nets for fellow citizens who fall on hard times. Yet each on inevitably turns into a lifestyle of subsidies. Too many government agencies measure success by the number of people who enroll in their programs, when true success would mean everyone is able to take care of themselves. That, however, would mean that the agency no longer has a reason to exist, which creates backwards incentives.

Returning to a society without welfare is a tall order and will likely not be accomplished in our lifetimes. What we can accomplish, however, is a return to programs that are narrowly tailored for only those who really need help and that work to get more people off the program, not on it. This has the double effect of helping people become more self sufficient as well as reining in profligate spending.

We as citizens must demand accountability of both our elected officials and the employees who carry out the mandates of our Legislature. When the Division of Vocational Rehabilitation lost track of $5 million, the Legislature decided not to simply pony up the cash to cover it. Lawmakers wanted answers, and in the end the director of that division did the right thing and resigned.

I remain optimistic about the reforms begun under Alex Adams’ directorship of IDHW. Looking inward to fix the structural problems with government welfare, rather than simply asking for more money, is a promising start.

Bonus note for paid subscribers below:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gem State Chronicle to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.