According to the recent Gem State Chronicle reader survey, 54% of respondents selected property taxes as the top priority for elimination. As I discussed with Nate Shelman yesterday, property taxes are unique in that they are taxes on unrealized gains. If you bought your house 30 years ago for $50,000, you’re not taxed on that original purchase price but on its current assessed value, which in some neighborhoods could be close to $1 million.

However, there are some misconceptions about property taxes that I’d like to address.

Last night, I live-tweeted part of the Eagle City Council budget hearing. Unlike most cities in the Treasure Valley, Eagle chose not to raise property taxes, sparking debate about whether the city could continue funding promised services and projects. Several responses to my tweets suggested that cities are receiving unprecedented tax revenues due to the increase in home values over the past 15 years.

But that’s not how property taxes work. If the value of every property in the state doubled from last year to this year, your tax bill would not significantly change.

Why?

A Primer on Property Taxes

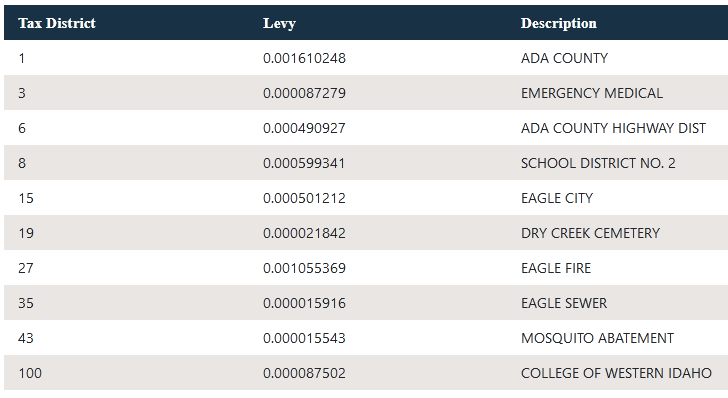

Every property is within at least one taxing district. For example, my home falls under the following districts:

Ada County

Emergency Medical

Ada County Highway District

West Ada School District

City of Eagle

Dry Creek Cemetery

Eagle Fire District

Eagle Sewer District

Mosquito Abatement District

College of Western Idaho

Some properties may be in more districts, some in fewer. Each district has the authority to levy property taxes to fund their operations. These districts are overseen by elected boards of trustees, who can — in theory — be held accountable for their budgetary decisions.

Throughout the spring and summer, each taxing district creates a budget for the upcoming fiscal year. Budget hearings are open to the public, who can usually provide comments. The revenue side of these budgets includes not just property taxes but also park fees, federal grants, and other sources.

State law constrains the property tax levy portion of budgeted revenues to a maximum increase of 3% per year, plus increases for new construction, and something called “foregone.” Foregone is when a taxing district declines to raise taxes one year but reserves that amount for future budgets. At last night’s meeting, the Eagle City Council unanimously voted to reserve nearly $150,000 in foregone tax increases for future use.

New construction taxes have been capped since 2021, when House Bill 389 set the maximum tax increase for new construction plus base property taxes at 8%. If a city takes the maximum 3% increase, it can only increase taxes on new construction by an additional 5%. H389 also restricted how much foregone tax revenue could be reserved at a time.

Once a district sets its property tax levy, taking these restrictions into account, its board votes to approve the budget. But how does this impact your property tax bill?

While taxing districts are finalizing their budgets, your county assessor is determining the value of every property in the county. Assessors consider home sales, market fluctuations, and other factors to determine the value of each property. Property owners receive their assessments — I received mine in late spring — and have a period to appeal if they believe the assessor's value is incorrect. The final decision on these appeals rests with the county commissioners.

Assessments typically rise during strong market years, which can cause homeowners to panic, fearing their taxes will rise accordingly. Take a deep breath and keep reading.

Once assessments and appeals are complete, the assessor has a comprehensive list of all taxable properties within the county. By adding up these values for each taxing district, they determine the total taxable value in each district.

Now it’s time to put the two things together. Each district’s property tax levy is divided by the total taxable value, resulting in a small number called the levy rate. Multiply that by your assessed value, minus any applicable homeowner’s exemption, and you have your property taxes for that district.

Add the levy rates for all the districts your property is in, multiply by your taxable value, and you have your total bill.

Still confused? Let’s take a look at my own bill as an example.

Each taxing district has its own levy rate. These districts overlap but aren't identical, so the total taxable value their levies are divided by differs. The total levy rate for my home is 0.004485179. The assessed value of my home in 2023 was $536,600. After subtracting the homeowner’s exemption of $125,000, my taxable value was $411,600. Multiplying by the levy rate and adding the amounts for each district gives me a tax bill of $1,846.12.

For the math-savvy, you might notice that multiplying by the total levy rate instead of each individual rate added an extra two cents to my bill. This is due to rounding when multiplying by each levy rate.

My bill also included an additional $7 for Drainage District #2, bringing the total to $1,853.12.

House Bill 292 last year reduced property taxes by shifting surplus state revenue to property owners. My tax bill showed two reductions totaling $156.44.

As you can see, your assessed value doesn’t directly determine your tax bill; it affects your share of taxes within your district. If only my home’s assessment doubled, while all others stayed the same, my taxes would increase significantly. But if all properties saw their assessments double, my taxes wouldn’t rise, because the levy rate would adjust accordingly.

Let me say that again: Your home’s assessed value affects your tax bill in that it determines your share of the property tax levy in each district.

This is why many property tax relief ideas are actually tax shifts. For example, the homeowner’s exemption shifts taxes onto businesses and second homes. Some suggest that retirees shouldn’t have to pay property taxes, but that would shift the burden onto younger families. Even the property tax relief from H292 shifted taxes onto small businesses.

Of all the tax schemes in our society, I believe that property taxes are the least moral in that they tax the unrealized value of our homes. Unlike sales taxes, which are levies on consumption, and income taxes, which are levies on earnings, property taxes are levies on what you own.

All taxes influence behavior. That is why some localities levy extra taxes on alcohol and cigarettes — they are trying to decrease consumption. Taxing goods reduces purchasing power; taxing income discourages productivity; taxing property makes it harder to buy and keep a home.

If we accept that some form of taxation is necessary, we need to discuss which taxes are most fair. That discussion starts with an understanding of how these tax systems work.

Property taxes may be the most immoral form of taxation, but the silver lining is that they are the most responsive to public pressure. Income and sales taxes are set by the Idaho Legislature, but property taxes are determined by the dozen or so taxing districts your property falls within. Do you know who is on your city council, county commission, and school board? Who is deciding the budget for your cemetery district or community college? Take the time to read their budget proposals, attend open hearings, and share your opinions. Call up board members and tell them what you think.

If all else fails, run for those positions yourself. While big roles like city councils and county commissions are usually contested and expensive, trustees for smaller boards like cemetery districts often run unopposed. Put your name on the ballot, get on a board, make some decisions, and learn more about the system in the process.

To reform a process, we must first understand the process. I hope this has been helpful in demystifying property taxes and prepares you to hold your elected boards accountable for their decisions.

Bonus note for paid subscribers below:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gem State Chronicle to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.