“Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country.”

(Attributed to Horace Greeley, 1865)

The years following the Civil War saw millions of Americans heading west to stake their claims to a new region of the New World. Congress was busy dividing up the territory, drawing lines on the map, appointing governors, and admitting new states. In the course of a single year starting in the autumn of 1889, six new states were added to the Union, including Idaho.

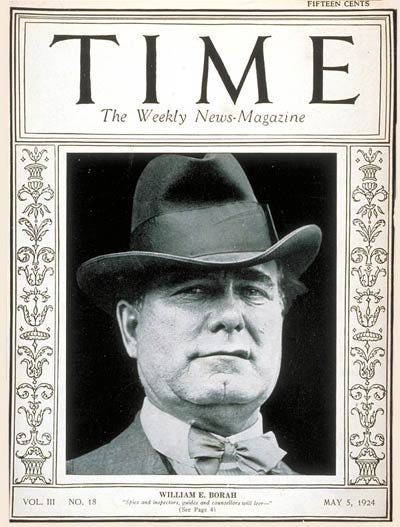

The very same year that Idaho achieved statehood, a young attorney named William E. Borah traveled to Boise by train to seek his fortune. He later said that this was as far west as he could afford to go. Within just a few years, the ambitious young man was elected chairman of the Idaho Republican Party, became secretary to Governor William J. McConnell, and in 1895 he married the governor’s daughter.

In the late 1890s, Borah joined with many out west in support of the populist presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, an advocate of free silver, a policy that challenged the gold standard of American currency at the time. Proponents of free silver claimed that it would level the playing field between poor western farmers and the rich eastern robber barons who controlled American industry. This would not be the last time that William Borah would stand up to powerful interests in the name of the American people.

By the early 1900s, many populist ideas had been adopted by the Republican President Theodore Roosevelt. William Borah was an enthusiastic supporter of Roosevelt, which cost him when Idaho’s old guard Republicans opposed his campaign for the US Senate in 1903. At the time, senators were appointed by state legislatures, so a senate campaign meant gaining the support of candidates for the legislature. Borah supported a measure that would allow senators to be elected directly by the people, and once in office he helped pass the 17th Amendment that did just that. (Ironically, the current Idaho Republican Party platform calls for repealing the 17th Amendment.)

By 1907, Borah had gained enough support to secure his appointment to the Senate, where he became a staunch ally of President Roosevelt, while clashing with his successor William Howard Taft. Borah attempted to walk a fine line between advocating progressive policies that would help the working men of America while opposing measures that increased the power of the federal government. He made a splash in Washington with his ten gallon hat, but gained a reputation as a skilled debater and orator.

Former President Roosevelt became disenchanted with his successor Taft and challenged him for the Republican nomination in 1912. Roosevelt had widespread support, including from Senator Borah, but Taft’s control of the party allowed him to win the nomination. Roosevelt took his supporters and formed a third party, but Borah refused to leave the GOP. Taft and Roosevelt split the right-wing vote in Idaho and in the rest of the country, allowing the progressive Woodrow Wilson to win with a mere 42.5% of the popular vote. (I wrote about the dangers of third parties in this newsletter.)

Senator Borah returned to Washington to oppose many of President Wilson’s initiatives. Despite supporting the 16th Amendment, which created an income tax, Borah opposed the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, fearing that it would bring the American economy under the control of wealthy bankers. (He was right.) When Wilson championed the creation of the Federal Trade Commission to protect consumers against big business, Borah opposed it, fearing it would simply allow big business to set government policy. (He was right again.)

Senator Borah continually argued against American interference in foreign affairs. He denounced the Wilson Administration over their policies of dictating policy to Mexico and South America, and when the Great War erupted in Europe in 1914, Borah spoke out against any special treatment of the Triple Entente. He supported a bill that would outlaw arms shipments to countries engaged in war. Nevertheless, President Wilson found a loophole by sending arms to Britain and France in exchange for “credit”.

By 1917, after several years of enduring unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany, Senator Borah reluctantly voted to declare war. In 1919, however, he opposed ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, and along with it, President Wilson’s cherished League of Nations. Wilson took America to war to gain a seat at the table that would reshape the world in its aftermath. He claimed the war was necessary to “make the world safe for democracy,” and he went to Europe (the first sitting president to do so) with a list of fourteen points by which he sought to influence the postwar world. The League of Nations, a supranational organization that would ostensibly make war obsolete, was Wilson’s crown jewel.

Senator Borah emerged as the leader of those who staunchly opposed tying the United States to such a foreign alliance. He went on a tour of the country speaking out against Wilson’s treaty. "America has arisen to a position where she is respected and admired by the entire world," he said. "She did it by minding her own business.”

In this, Senator Borah was walking in the footsteps of many great American statesmen, most notably John Quincy Adams. Adams was the son of a president, Secretary of State to President Monroe, president in his own right, and then he spent the remainder of his life in the House of Representatives, passing away in the Capitol Building. He crafted the Monroe Doctrine, which discouraged European powers from continued interference in the Western Hemisphere, but he also defended American neutrality. “Wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.”

On November 19th, 1919, Senator Borah spoke in opposition to the Treaty from the Senate floor. For two hours, and without notes, Borah argued that the United States must not enter this alliance. He hearkened back to the farewell address of President George Washington, who exhorted us not to become entangled in European alliances. His address moved the chamber to tears and strengthened the resolve of the Republican Party to vote against the treaty. It came up for three separate votes over the next four months, and was defeated every time. The great orator from Idaho had prevailed against President Woodrow Wilson.

Senator Borah continued fighting to put America first for the rest of his career. In his final major speech in October of 1939, just days after Adolf Hitler invaded Poland, Borah once again spoke in favor of American neutrality. He died in 1940, less than two years before the United States would enter World War II.

Unfortunately, there were no William Borahs in the US Senate in the aftermath of that conflict, nobody to steel the resolve of the Republican Party to oppose our entry into more and more supranational organizations. Today, we hand over our money and our sovereignty to groups such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization, all in the name of global peace and unity. But as Senator Borah taught us just over a century ago, American peace and prosperity is built on American neutrality. It is not isolationism, as critics contend, to avoid entangling alliances that only feed the military / industrial complex. It is prudence. It is what putting America first is all about.

William Borah went west to grow with the country, but spent his career representing Idaho in the federal capital back east. In a way, his country grew beyond him, as the America of his youth transformed into the empire we know today. Through it all, Borah steadfastly represented the promise of the old America, the America of John Quincy Adams, of Horace Greeley, and of the pioneers who tamed the west.

As the drums of war beat louder and louder this year, demanding we send money, equipment, advisors, and eventually American troops to eastern Europe, let us remember the life and lessons of the great orator from Idaho, Senator William E. Borah.