This morning, the Citizen’s Committee on Legislative Compensation met to discuss lawmaker salaries. The committee convenes every two years to set pay for incoming legislators.

Idaho has maintained a part-time Legislature since statehood in 1890, with lawmakers working January through April before returning to their regular lives. Currently, legislators earn $19,913 annually, along with a per diem of $74 for those near Boise and $221 for those farther away. The base amount is meant to cover meals, while the extra is for lodging.

But is serving in the Legislature truly a part-time job? Legislators work long hours during the session and continue engaging with constituents and legislative duties afterward. They also campaign for reelection every two years, though on their own time.

This part-time salary structure limits the job to the retired, independently wealthy, self-employed, or those with employers who allow long absences. It excludes most working-class citizens who need year-round employment to support their families. I heard one candidate this year say that winning the election would pose a problem when it came to paying the bills.

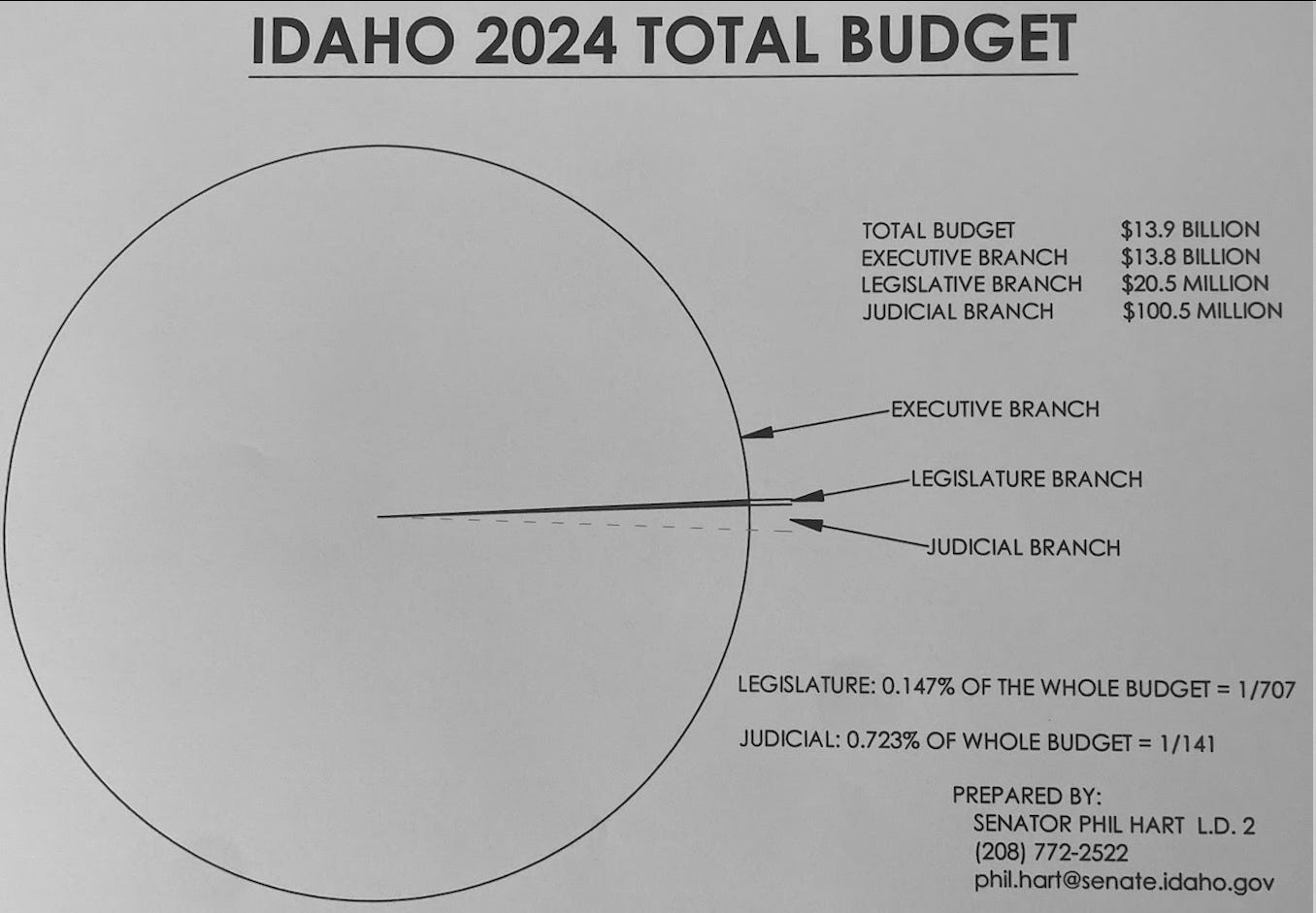

In any case, the discussion about our Legislature’s part time status and how much each member should be paid ignores a bigger issue. The Legislature is one of three co-equal branches of government, along with the Executive and the Judiciary. As part of our system of checks and balances, the Legislature is tasked with a certain level of oversight above the other two. Yet when it comes to resources, the Legislature lags far behind, with a mere 0.147% of the state budget.

Sen. Phil Hart did the math, and was kind enough to share his findings with me:

It’s easy to look at the situation and say the solution is simple: shrink the Executive Branch. But who will actually do that? The bureaucracy won’t limit itself, and it's the Legislature’s job to oversee the Executive as part of our checks and balances system. As it stands, however, this is like David overseeing Goliath. Lawmakers lack the resources to fully perform their constitutional duty of balancing the other branches.

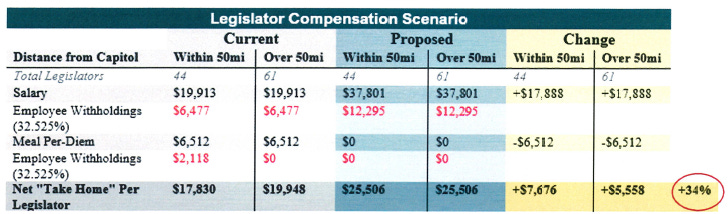

Ironically, those other branches hold checks on the Legislature by setting its salaries. The committee that met this morning consists of six citizens, three appointed by the governor and three by the Supreme Court. House Speaker Mike Moyle and Senate President Pro Tempore Chuck Winder presented a proposal to raise lawmaker pay by 35%, while eliminating the $74 base per diem:

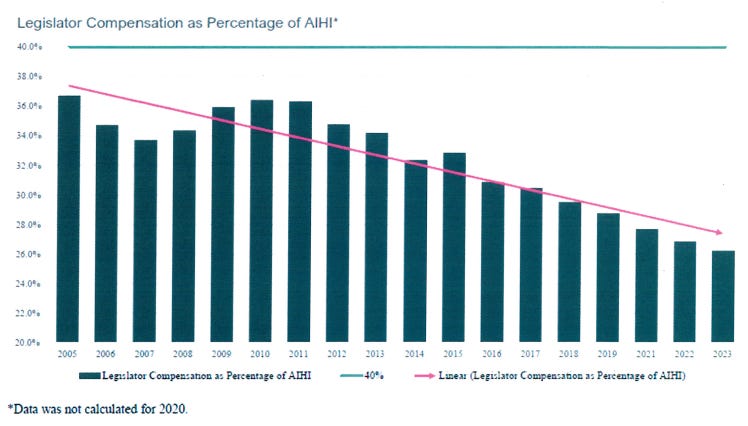

The proposal would peg legislative compensation at 40% of the Average Idaho Household Income (AIHI) index. According to the authors, this is a fair reflection of a legislator’s average workload. Currently, legislative compensation is just over 25% of the AIHI, and has been steadily dropping over the past two decades:

The committee split 3-3 on the proposal, deciding to reconvene on November 6 to seek a compromise.

Raising legislator salaries is always a tough sell, especially when the public often assumes they make far more than they do. While members of Congress earn $174,000 annually, state legislators earn far less, yet many voters assume their pay is comparable.

There’s also a misconception that Idaho lawmakers have staff to help draft bills, research issues, or handle constituent communication — resources available to members of Congress but not Boise legislators. A few wealthier lawmakers may hire personal assistants, and some rely on volunteers, but most handle their duties alone. House and Senate leadership have staff, committee chairs have a secretary, but most everyone else has to share a pool of attachés.

The pay gap between lawmakers and other state employees is stark. Some of Idaho's highest-paid public officials work in universities, such as BSU football coach Spencer Danielson, who earns over $1 million annually, and University of Idaho president C. Scott Green, who makes nearly $500,000.

Meanwhile, our lawmakers earn under $20,000 per year. The combined salaries of all 105 legislators is just over $2 million, roughly the same as five or six university administrators. Each session, legislators consider hundreds of bills, serve on multiple committees, and assist constituents with bureaucratic issues. Yet, we still label them "part-time."

This question isn’t about pay or whether we need a full-time Legislature. It’s about the balance of power between the branches of government. The Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Branches are constitutionally co-equal, exercising checks and balances against each other. Our Founding Fathers deliberately crafted our national government to have these checks and balances, drawing from the wisdom of Montesquieu and other political philosophers, and the founders of our state applied the same ideas here. Yet the current imbalance of power in Idaho government makes a mockery of checks and balances.

As the direct representatives of the voters, the Legislature is the first line of defense for our liberty — or, in the wrong hands, its biggest danger. Therein lies the rub: can we restore the balance of power by increasing the resources allocated to the Legislature without risking it becoming just as out-of-control and tyrannical as the bureaucracy?

Yet the bureaucracy is already out of control. The biggest difference between the two is accountability: legislators face voters every two years, while Executive Branch appointees and staff often serve for decades with little oversight. Former solicitor general Theo Wold has said that we continue to live under the administration of Democratic Gov. Cecil Andrus, since he appointed so many bureaucrats whose philosophies permeate the agencies to this day.

I don’t have an easy solution to this dilemma. I definitely want to see the Legislature reclaim its constitutional authority to act as a check on the Executive Branch bureaucracy, but I don’t necessarily want to see Idaho transition to a full-time Legislature. Perhaps a small pay raise, or a stipend to hire a full time staffer would be enough to begin restoring the balance of power.

While some on the libertarian or anarchist side of the spectrum would be happy to have no government at all, I think most conservatives desire government to be small, but good. We get the government we pay for. Are we paying enough? If the lawmakers on JFAC were able to hire full time staff, would that make them more effective in reducing state budgets?

What do you think? Having read all of that, please take a moment to answer the survey questions below. I will share the results in a week. I hope this article starts a positive conversation about the structure of our government and how we as citizens and voters can take a stronger role in bringing our government back to its foundations.

If you circle back to my proposal to give the Senate and the House separate legal offices, you will find it not only removes the power of the executive to influence the laws created by the legislature through opinions, but it also provides attorneys who can review all of IDAPA (722 sets of rules) and then issue reports to the leaders of the legislature every year prior to each session where the legislators could during the session make changes to the body of executive branch rules.

That is not just looking at the new rules as they come from the executive branch every year, which is the untenable method used now, but the whole body of rules needs review and cutting back.

I don’t think Idaho will fix any balance of power issues or separation of power issues by giving the legislators a pay raise, although it may be helpful to draw better representation from the populace. The way to fix a lack of legislative power is to give the legislature more power, so give them their own legal counsel so they can actually monitor the executive branch all year. These would be full-time jobs, partially so there is no need for a full-time legislature.